Training Zones: What is the point of training zones?

This is just a quick post inspired by some custom analysis I have been doing on my athletes’ race files.

This is a basic question and every knowledgable athlete and coach knows the answer, right? While I do believe this is mostly true, it is also easy to get caught up in the conventional wisdom and simply apply the popular systems without examining whether there are better approaches.

The short answer is that training zones are utilized as a shorthand for the intensity-duration relationship and help us to easily describe and prescribe workouts and training intensity.

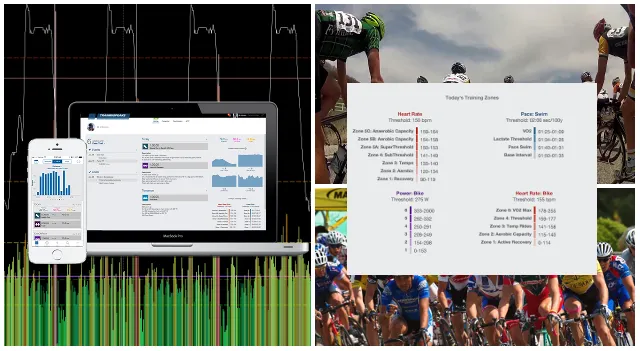

There are many different zone systems in use today. Obviously, there are zone systems based on heart rate and power, but also muscle O2 saturation, torque/force, and pace. Some systems were born in the lab and have a long history of use within the scientific community. Other have emerged to take advantage of the steady stream of new consumer devices that have made it to market over the last couple decades. Many systems were developed to provide value to specific communities, e.g., recreational athletes working out primarily in gyms.

Probably the most common system in use in the power-enabled cycling community is the 6-7 zone system published by Dr. Andrew Coggan and Joe Friel in the book Training and Racing with a Power Meter and implemented in the Training Peaks software.

Regardless of the zone system we use, we should always remember why we want training zones in the first place: 1) to make it easy to communicate, and 2) to describe a relevant grouping of effort intensities that can be linked to specific underlying physiological demands, in simple terms: “similar efforts.”

This approach allows athletes and coaches to clearly understand what needs to be executed and link training to performance outcomes and/or physiological adaptations. Of course, no system is perfect in this regard and there are still substantial limits to our collective understanding of the underlying physiological processes involved in endurance performance. Nonetheless, we should make our best efforts to use an internally coherent approach within the limits of our current understanding.

As an example, let’s examine the so-called Sweet Spot zone. According to it’s “creator,” Sweet Spot describes efforts between 84-97% of estimated FTP (in watts).

Problem #1: This is not some previously unidentified portion of the power-duration curve, it simply claims the upper part of Zone 3 and the lower part of Zone 4 in Coggan’s Classic Power Zone system. As such, this isn’t really a new zone. Why create a new zone when you can simply describe an effort as “high Zone 3” or “low Zone 4”.

To be fair, Sweet Spot gained popularity because it is claimed to be a more effective than either Zone 3 or Zone 4 at increasing FTP. The claim is that Zone 3 does not impose enough aerobic strain and Zone 4 imposes too much, requiring additional recovery between sessions. Thus, training in this range is the “sweet spot” getting you the “the most bang for the buck.”

Notably, I have also heard of Sweet Spot defined more narrowly as the point of transition between Coggan’s Zone 3 and 4, so specifically 90% of FTP. This seems more consistent with the rationale above and is usually how I prefer to use the concept of “Sweet Spot”. I also prefer this latter approach because it makes more sense grammatically, i.e., “spot” as a specific point rather than a range.

Problem #2: Given where the “sweet spot” sits on the power-duration curve, the defined range (84-97% of FTP) is too broad to be describing similar efforts.

A 97% of FTP effort is quite high and is something that most riders will not be able to sustain for much over 60 minutes (and will infrequently perform more than 20 minutes with any frequency in training). So, the upper end of the “zone” is duration-limited as it is very close to the maximal steady-state effort the rider in question can sustain. Further, it puts maximal strain on the fuel system, burning glycogen at a very high rate. This will further limit the amount of time that can be spent at this intensity without significant attention to fueling.

On the low-side, an 84% of FTP effort is something quite different. Such an effort could be sustained for multiple hours. Obviously, this would be a taxing effort, but it is physiologically possible.

From a subjective perspective, athletes are very likely to feel different at the high and low of this range. A 20-minute effort at 84% of FTP will feel quite a bit easier than 97% of FTP.

I suppose one could counter that it is enough to prescribe “low Sweet Spot” and “high Sweet Spot.” This is technically true, but seems silly and confusing to me. Why have two different names to describe the same intensity ranges?

I prefer to think in terms of functional intensity targets

For example, if you are training for a 60-minute steady effort (TT), then training around the intensity you can sustain for about 60 minutes is specifically targeted to your event. This might well be around 97% of your FTP.

On the other hand, if your goal is a long MTB or gravel event, you might focus significant training time on the maximal intensity you can sustain for the 6-8hr duration. This might well be around 78% of your FTP.

Similarly, let’s say you want to work on your ability to make 1-2 minute maximal efforts late in a 60-mile road race. Do you really need to know what zone that is? If you need a reference wattage target simply use your own 1-2 minute best efforts. Do efforts at or near the target watts at the end of your 2.5-3hr rides and monitor for improvement over time. Easy, peasy!

Bottom Line

Of course, there is much more to be said on the topic of training zones in general and individual zones, specifically. The point here is to shine some light on the rationale behind and limitations of training zones and encourage athletes and coaches to not limit themselves to the system with the most active marketing department.

Train smart! Race smart!